The following text and poem are from the short book Calvin White wrote and self-published for his family and friends in 2015. A large version of the poem was displayed in my Gallery in the Orchards Centre, Dartford. Limited copies on A4 sheets were available free of charge.

11AM Sunday 3rd September 1939, the Start of the Second World War

My name is Calvin White. I am five years old. It is a bright sunny day in Camberwell, South East London, where I was born. But at about 11.30AM, large spots of rain started to fall. Mum said they were tears from Heaven.

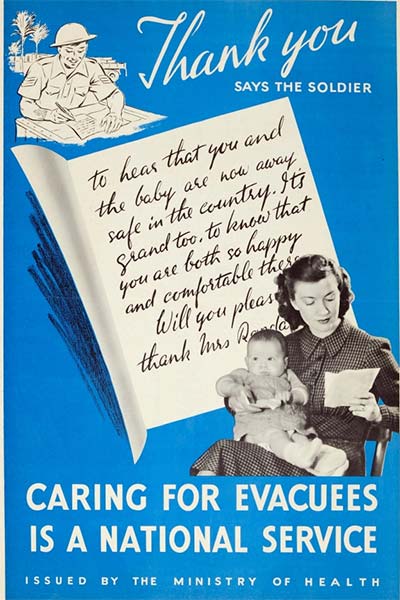

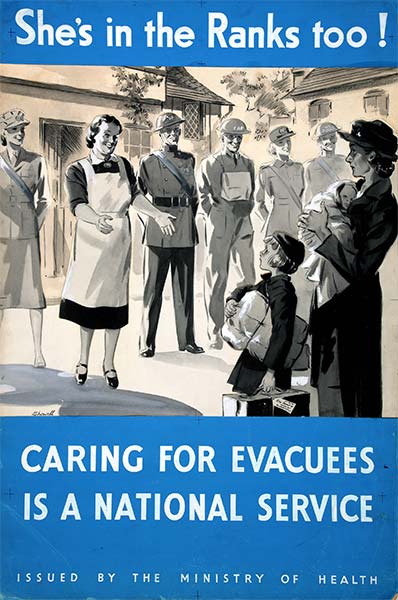

One week after the declaration of war, two coach loads of children, some with their mothers, were evacuated from our school in Camberwell to Wootton Bassett in Wiltshire. If you were aged five years or over, you were sent on your own, or with older brothers or sisters. If you had a sibling under five, your mother was evacuated with you, so as my sister Maureen was only three, our mother came with us. When we arrived in Wootton Bassett, there was a great deal of confusion, as due to a mix up with paperwork the authorities were only expecting about half the number of evacuees that actually arrived. Half were placed with the volunteers that had said they would be willing to board evacuees. These people were paid ten shillings a week for children, and I think double that for mothers. The average wage for workers in 1939 was between two and three pounds per week

The local council and the WRVS (Womens Royal Voluntary Service) tried their best to get the remaining evacuees housed, but only about half were placed. It was more difficult to get accommodated if the mother was with their children, perhaps due to lack of room, or maybe the woman of the house didn’t want another woman in her house and sharing the kitchen.

The remainder of the evacuees including us (about twenty people altogether) had to sleep on the floor of the church hall. Local people were asked to lend any spare bedding they had. We slept there for three nights. Food and drink was supplied by the WRVS.

It must have been embarrassing and distressing for all the remaining evacuees, because the people who were going to accommodate them were invited to select the ones they wanted. Some people only wanted one, which meant brothers and sisters were often split up. Big problems arose, as they could end up going to families in different villages, and attend different schools.

In 1939 only very wealthy people had cars, so there wasn’t much movement between villages. It was possible that brothers and sisters might not see each other for long periods, if at all. The authorities did their very best to keep families together, but it wasn’t always possible. Some children who were evacuated for years returned home after the war speaking with a different accent to their parents. Some might have forgotten what their families looked like. It was a great upheaval.

Evacuees had mixed experiences. Some were treated and looked after very well, but others were not. In fact, some were very badly treated, some people only wanted the children for the money, and their rations. Some children were abused.

As only the rich had telephones, no contact could be made in this way between evacuees and their families. The only means of contact was by letter, which was not an option for young children without assistance. Correspondence could also be vetted by the host families, so many children were left without any means of alerting family if they were unhappy.

Back in Wootton Bassett, three days passed without us finding anywhere to stay, so my mum decided to take us back to London.

My father had been conscripted into the army three months before war broke out. He was thirty six years old. I remember going to Surrey to visit him with my mother, all the troops there were living under canvas. My father became ill through the effects of a duodenal ulcer, and was transferred to the Royal Herbert Military Hospital in Woolwich.

On various occasions mum and me travelled from Camberwell by tram to visit him. On the first visit, dad had a present for me. It was a recorder. I probably drove everyone mad by forever blowing it. Despite extensive treatment, dad’s health didn’t improve, and he was given a medical discharge from the army. As he had been a regular soldier as a young man, serving in India, Burma (now Myanmar) and Mesopotamia (now Iraq) he was given a good position at the Royal Arsenal armaments factory in Woolwich, as an inspector. This was a very dangerous place to work, as all sorts of weaponry was made there, including bombs, shells, and hand grenades. There was always a risk of accidental explosions, and the risk of being bombed in air raids, as the site was a prime target for the Germans.

At the beginning of the war, everyone was issued with a gas mask. There was a fear that the Germans would drop bombs containing poison gas, which would kill a very large number of people. The masks were made of black rubber for older children and adults. They had a very strong smell which made people feel sick, and it was not easy to breathe in them. You had to carry the gas masks everywhere you went. People were asked to gradually increase the wearing time, so they would get used to them, in the event of a gas attack. There was a special filter on them to stop the poisonous gas getting into your lungs. Very young children were given masks that looked like Mickey Mouse, but children hated the smell, and they were uncomfortable to wear. The type babies were given were like containers, that the baby had to be placed in. Fortunately, poison gas was not used in the war by either side.

Back in London, there was no bombing. In fact, a full year passed with no air raids on Britain. Hitler’s forces were too busy invading other countries in Europe. This all changed in September 1940, with prolonged heavy bombing raids, as hundreds of German planes bombarded London nonstop for fifty seven days and nights. The result of this onslaught was death or injury to a huge number of civilians, and the destruction of large areas of London. Other cities and towns were also bombed. The Germans called this the ‘Blitzkreig’ (an all out battle to obtain a quick victory) which was shortened to ‘The Blitz’. To escape the danger, many people used to take bedding to underground stations, and sleep on the platforms, even though trains were still running. At first, the government tried to ban this practice, but relented to pressure as the bombing got worse. Heavy bombing continued, but occasionally there would be a day with no attacks at all. Planes continued to drop bombs on London, and the rest of Britain to a lesser degree, for the next two and a half years.

Some people travelled to Chislehurst Caves while the bombing was on, to shelter deep underground. Each person was given a number, which was matched with an allotted place in the caves. They would leave their bedding whilst they went about their normal business during the day. When they arrived at night, they had to sign in. If someone didn’t turn up for three successive nights, it was assumed they had been killed or injured, and their space was given to someone else. The authorities tried to make the caves as pleasant as possible. There was a cafeteria, dance floor, cinema, chapel and a first aid area. Entertainers used to visit to put on shows for people. There were marriages in the caves, and a baby was even born down there.

Our house in Camberwell had no garden, only a small courtyard at the back, which meant that we were unable to have an Anderson air raid shelter installed. These shelters had to be inserted into an area dug to a depth of around five feet, with a metal rounded roof, and then covered with about two feet of earth.

When the air raid sirens sounded (which was very frequently) my mum, Maureen and I used to sit under the stairs, which was considered to be the safest place in the house. During these bombing raids large anti aircraft guns were firing at the German planes overhead. These guns, and large searchlights to help spot the approaching aircraft at night, were situated in parks and open spaces. The people that operated these had to live in tents all year round, in all kinds of weather, so that they were always there when needed. The noise was horrendous. My sister and I were too young to realize the danger we were in, but my mum must have been terrified, especially as my dad was working twelve hour night shifts. All lights were banned at night, as these would show German bombers that there were cities or towns below. This was known as the Blackout. Anyone showing any light, even the smallest chink, could be fined or even imprisoned. Black curtains had to completely cover all areas where light may show through. There were no street lights, all lamp-posts and poles had white rings painted round them, so people didn’t walk into them, and kerbs were painted white to show drivers where the road was. All vehicles, including bicycles, could only have dipped blue lights. Buses and trams had black blinds fitted to the windows. Due to the complete darkness, lots of accidents occurred, car crashes, people being knocked down, and people tripping and falling. Some people used small torches with blue bulbs, that had to be kept dipped, but most decided to stay in after dark, especially older people. It was especially hazardous in the winter months, when people had to travel to and from work in the dark.

To escape from the blitz, my mum, my sister and I went to live in a village called Timsbury in Somerset. Some of our family had been evacuated there, and said it was a nice safe place. An elderly man who lived alone said that as we had evacuee status, we could live with him in his cottage. I remember being in the fields and watching dogfights, a name given to air battles between German and British fighter planes, such as Spitfires, Hurricanes and German Messerschmitts. The pilots used to battle very high up, so that if their planes were damaged, they would be able to parachute down. I saw many planes shot down, and pilots parachuting in the distance. The German fighter planes were sent to protect their bombers that were on their way to attack Bristol, a very important port and manufacturing base. We didn’t stay in Timsbury for very long, about two or three months. My mother’s sister Mary, who was single and lived in London, contacted my mother to say she was going back to Ireland to escape the bombing. Mum and Aunt Mary had been born in Belfast. Aunt Mary suggested that as my mother was pregnant, she and us children would be safer, and better looked after by herself and other family members in Belfast. My dad, who was English, agreed to this. We arrived in Ireland in late 1940, and moved in with Great Grandmother Matthews. She lived in Frederick Street, Belfast. She had three sons. One of these, my mother’s father (my grandfather) had died in the great flu epidemic following the end of the First World War. The other two sons became priests. One was based in St Patrick’s Cathedral, Belfast. The other became a missionary priest in Monrovia, Africa, and finished up in charge of a large area there. We didn’t stay long with Great Grandmother Matthews. I think all the extra people in the house was too much for her. Mum and Aunt Mary went looking for new accommodation, and rented self-contained rooms above a pub. Northern Ireland hadn’t been bombed up to this point. People thought that as Southern Ireland was neutral in the war, and was therefore obliged to refuel German submarines, the German’s would not bomb Northern Ireland for fear of upsetting Southerners who most likely had relatives over the border. They were wrong. My sister Sheila was born on 4th March 1941. Soon after this, German broadcasts said that Belfast would be getting Easter eggs, meaning bombs. The bombing of Belfast over the Easter period caused terrible damage to property, especially the dockland area. Many people were killed or injured. Some of the bombs were landing quite near to where we were living, so we used to go down to the basement of the pub we were staying above, as there were no air raid shelters available. The noise was horrendous, but we were lucky to escape without injury, or worse, as all around us were ruins and fires caused by the bombing. The pub only suffered minor blast damage. Nobody in our family was injured, but we were very shocked. We had to get out of Belfast quickly, as more raids on the docks were expected, and we were living close to them, only about half a mile away.

We moved from Belfast to a farm in a very small village called Ballymaguigan in County Antrim. This was only a short distance from Lough Neagh, the largest lake in the British Isles, measuring over a hundred square miles. I don’t know how we came to live on the farm, I can only assume that family or friends knew the farmer. The village was very isolated. The farmer and his wife had five sons and five daughters, and they all lived at the farm. I remember mum and Mary saying that they were still living in the olden days. They lived mainly on what they produced on the farm, no luxuries at all. I was given the task of collecting all the chicken and duck eggs. These would be in all different places, as the chickens and ducks roamed free. The family owned a number of fields down near the lough, in which they grew flax, a plant with small blue flowers. The flax, when processed, is turned into linen. There were many linen mills in Belfast. Mum and Mary worked in one of these mills when they first left school. Ireland was famous for its high quality linen.

One of the farmer’s sons used to take me down to the flax fields. We went by horse and cart, it was a shire horse. The horse had to be strong as the cart was always heavily loaded, and had to be pulled up a very steep hill back to the farm. The farmer’s son used to whip the horse a lot to make it pull harder. It made me angry, and I would tell him to stop. He said if he didn’t use the whip we would never get back to the farm. After a few of these trips, I told the farmer’s son that I didn’t want to go with him anymore.

There was very little privacy for us at the farm, and it was also very crowded. Mum and Mary were not happy living there. One day, while we were out walking, they met an old man and started talking to him. They told him about living at the farm, and that they were looking for somewhere else to live. He told them that he had recently moved out of a three roomed stone cottage that he owned. He had gone to live with family as he couldn’t manage on his own any more. He told mum and Mary that they could rent it. It was still in Ballymaguigan, so we need not move far. The old man took us to look at the cottage. It was very small with tiny rooms. None of the village homes had running water, electricity or gas. There was only one fireplace, and the only fuel was peat. The toilet was in the back garden, and the bucket under the seat had to be emptied into a cesspit, and covered in soil. Mum and Mary asked how much the weekly rent would be, and the old man asked if five shillings would be alright. They said they couldn’t possibly pay as little as that, and said they would pay him ten shillings a week. We left the farm and moved into the cottage. It was furnished, but very sparsely. It had bare stone walls inside, and a stone floor. The village did not have a water pump because it was built on top of a hill, and electricity has to be available to pump water uphill. To get water we had to walk across two fields to a small river, fill a bucket, and carry it back. I often had to do this. A bucket of water is heavy, especially when you’re only seven. The water always had small things swimming about in it, no matter how careful you were trying to avoid them. The water had to be boiled over the peat fire, and then drained through an old piece of fine lace curtain to filter it. My sister Sheila was only a small baby, so I don’t know how my mum coped. There was a small house in the village that doubled as a shop, but it had a very limited stock. Milk was sold out of the churn, straight from the farm. The village was virtually cut off from what was happening in the war. This was because there was no electricity, which meant no telephones or radios. There were also no newspapers. The only contact we had from the outside world was from dad’s letters, which also contained money.

On occasions some of the villagers would spend an evening with us to chat about things in general, but especially about mum and Aunt Mary’s lives growing up in Belfast, and then later on in London, and their experiences of the war. The Irish love to tell ghost stories, so quite often the conversation would turn to this subject, with everyone giving their own versions of ghostly tales. Mum and Mary told them about their own experience of living in a haunted house in Belfast when they were young. There were no internal doors in the cottage, so although I was in bed (and thought to be asleep) I could hear all these tales, which was very frightening. The Irish country folk believed in banshees, a female spirit whose wailing supposedly warns of a death in a house within hearing distance. They also believed that if a dog kept howling someone nearby was going to die. I know now that the banshee sound was probably a fox during mating season.

The school I attended was about a mile away. A boy who lived close by, aged about twelve, used to take me to and from school. Children started school aged five, and left at fourteen. We had to walk there and back in all sorts of weather, including snow. We had no umbrellas, if our clothes got wet they were put close to the peat filled stove to dry. On my first day at the school, all the other children stood around pointing at my feet. I wondered why, until I realised I was the only child wearing shoes. I felt like the odd one out. Their parents could not afford to buy them any. The school was very small, just three rooms. We had to sit on long wooden benches. There were no chairs or desks, no books, pens or pencils. Each child had a framed slate and chalk. Everything we did in lessons had to be written on the slates, and then rubbed out when it got full. There was no record kept of any work the children did. Every child had to take their own food and drink. Food was very basic, no sweets or cakes, mostly bread and cheese, boiled bacon, boiled eggs and fruit. There was just milk or water to drink. I nearly always had a little treat or two in my lunchbox, but I kept them out of view as the other children would have wanted them (I knew what I was doing!). Looking back now, it would appear to have been more like a Victorian school than a 1940’s one.

We left Ireland in late 1941, and returned to Camberwell, London. I don’t know why, as London was still being quite heavily bombed. We had a few more narrow escapes, so mum and us children were evacuated again. Aunt Mary decided to stay in London this time. We were sent to a village in Suffolk called Alpheton, about three miles from Lavenham. We lived in the Old Rectory, a beautiful old black and white building, which was about three hundred years old. The rectory had been sold to an admiral prior to the war by the church, and the resident rector moved to a house close to the church, about half a mile away. During the war, the government could commandeer anything they wanted to. This may have been the case with the Old Rectory. The powers that be decided that the rectory could accommodate four mothers and their children from London, and an appointed government employee would be in charge. Her name was Mrs Winters. Mum, my sisters Sheila and Maureen, and myself arrived in Alpheton in early spring 1942. The other three families had already settled in, and all four mothers were expected to do all the cooking and cleaning on a roster system. This was a wonderful place to live. There were two ponds, with ducks and moorhens, a small river with fish and newts, and a large orchard with apple, pear, plum and greengage trees. We were allowed to help ourselves to fruit as soon as it was ripe. By the side of the rectory were two large walnut trees, and a large fig tree. One day Mrs Winters obtained four white ducks. These ducks laid eggs that were reputed to be a different colour to the eggs laid by the ducks already at the rectory. However, no eggs could be found, even after the ducks had been in the grounds for about two weeks. The ducks were reported to be good layers. Mrs Winters said that she would give one penny for each egg found. You could buy quite a few sweets for a penny back then! One day, I was looking out of our bedroom window, when I saw a white duck walk into the small wood in the grounds, about sixty yards from the ponds. A short while later I saw another duck go into the wood too. I went downstairs, followed them into the wood, and found that the ducks had been laying their eggs there. I found eighteen eggs! Mrs Winters gave me one shilling and sixpence. This amounted to three weeks pocket money. No more money was paid for eggs, as everyone now knew where they were being laid.

In the grounds there was a really big tithe barn in which we could play. ‘Tithe’ in old English meant a tenth. A rector was entitled to a tenth of all the products produced by his parishioners, which he could use or sell. A vicar, by contrast, was paid a stipend which was a yearly wage. Being a rector was a higher position in the Church of England than a vicar. The tithe barn was used to store the proceeds given by the people of the parish. Mrs Winters was a very upper class and educated lady. She was also very kind. She bought all us children a rabbit each, and let us name them. She bought all the hutches, and had a rabbit run made. She was a keen gardener too. There was a very large kitchen garden in the grounds. Mrs Winters divided it into small plots, and gave one to each child that was old enough to look after it. She bought lots of seed packets, which included flowers and vegetables, and showed us how to sow them. The rectory had a long drive leading up to it. When we first arrived it was lined with thousands of snowdrops. They were followed by a huge number of different coloured crocuses, the after that, daffodils. I am sure I obtained my love of gardening from my experiences in Alpheton.

There was also a small wood in the grounds, with lots of old and large trees. We were allowed to make a treehouse in one of them. It was great fun. On non school days at 11am, the kitchen window would open, and one of the mothers would ring a large bell to let us children know that it was ‘elevenses’ time, and cakes and biscuits were served. All of us children had to be in bed by 8.30pm, except in summer months, when we were allowed to stay up until 9pm. This gave the mothers some time on their own.

All the children of school age had to wait at the end of the rectory drive for the school bus to arrive each morning, to take us to a school about five miles away, as there wasn’t a school in Alpheton. The school was in a village called Shimpling Street. The school building consisted of two large rooms and one small room. The small room was for infants. I was in one of the large rooms, which was divided in two by a large floor to ceiling curtain. This enabled two different age groups to be taught, but it also meant each class could hear everything the other class was doing! At the rear of the school was a large field for playing in. There was also a playground. Some of the village ladies used to prepare dinners for the school children. They worked as a group, and the meals had to be ordered in advance. One day, Mrs Winters told me that she was going to drive to a town called Bury St Edmunds in her little black car, that was lent to her by the government, and would I like to go with her. I said yes because I had never been in a car before, so I was very excited. The town was about ten miles away. While in town, she took me into Woolworths and bought me a present. She seemed to like me. I celebrated my ninth birthday on October 2nd, 1942. Whenever it was a child’s birthday a small party would take place. Nothing fancy, but enjoyable. Mrs Winters had only one fault, and that was her passion for quince jam, which she made herself. There were quince trees growing down by the small river, she used the fruit from these. The jam was spread on the bread when we received it, and as it was wartime, nothing must be wasted. All of us children hated the jam, especially me, but as Mrs Winters said she had made it just for us, we ate it. It was a pity there was not a dog in the house, for then I could have put my portion under the table for it to eat, but thinking about it now, the jam was so horrible I doubt even a dog would eat it.

Christmas 1942 at the rectory was a happy occasion. A fir tree was cut down from the wood, and the mothers and children made decorations for it. During the war the Americans sent toys at Christmas to be distributed to British children. Some of these toys arrived for us at Alpheton. Nothing big, just small toys, but we treasured them. I received a small metal aeroplane, but I didn’t have it long, as someone stole it from my coat pocket as it was hanging in the school cloakroom. The culprit was never found.

In the spring of 1943 all of the mothers and children had to leave the rectory, as it was being returned to its owners. I don’t know why this was, but we were all very sad to leave, and cried when saying goodbye to Mrs Winters. She returned to government offices in London. We were all transferred to a vicarage in the village of Acton, two miles from the town of Sudbury, so we were still in Suffolk. The vicar had vacated the vicarage to a smaller property, probably by order of the government. The woman put in charge of this place was not as friendly as Mrs Winters, she was more like a headmistress. The whole set up was different. No beautiful grounds, just an ordinary garden, which after Alpheton seemed very boring. The vicar kept a lot of geese in a large pen. The mothers were given the task of feeding them, and collecting their eggs. Geese can be very aggressive when you intrude into their territory, especially when you try to take their eggs. When anyone entered the pen they would stretch out their necks, open their beaks and make a loud hissing sound, and half fly, half run, at a fast speed towards any intruder. None of the mothers could get into the pen without being attacked. All were petrified of going anywhere near the geese, except my mum, who seemed to have a magical calming effect over them. She was the only one who could enter the pen without being attacked. Nobody could understand this. Mum accepted the job of looking after the geese full time.

All of us children that were of school age attended the Acton village school. We were not given the same welcome as the school near Alpheton, and felt a bit left out of things. At the vicarage the food was prepared by a paid cook, and wasn’t very nice. The mothers were unhappy with a lot of things at the vicarage.

Whilst walking along a country lane one day, on the outskirts of Acton, with another evacuee boy, we heard the engine of a plane flying very low, so we were on our guard. Children in the war years were warned to hide from low flying aircraft, in case they were German. Lots of people were machine gunned to death by low flying aircraft in the war. We dashed for cover under a group of trees and hid. Seconds later a German fighter plane flew over. It was a Messerschmitt. It was so low, we could see all the markings on it. We had a very lucky escape, as about a mile further on, the pilot shot and killed a farmer and his young son working on their farm. I think we would have been killed had we stayed on the lane.

Earlier in the war, one of our local milkmen, who pulled a hand trolley to deliver the milk, was shot dead by a German fighter plane on his early morning round in Camberwell. You had to be very careful for another reason too. German planes dropped butterfly bombs. These were very small in size, but when they exploded, could kill people up to ten metres away, and inflict serious shrapnel wounds as far as a hundred metres. These small bombs were painted different colours. They were given the name butterfly bombs because when they were dropped, two hinged flaps opened up in flight, looking like wings. They were mainly dropped in open spaces, such as fields, woods, parks etc. They did not explode when they landed, but each bomb had a spring loaded pin which released itself, and if anyone touched the pin the fuse would react and set the bomb off. They were quite often found hanging in trees and bushes. Children were shown pictures of them, and warned never to touch them, and to report them to an adult.

Mum was not happy living in Acton, so we returned to London. German planes were still bombing London, but less frequently than before. After a short period, our family were given the chance to move to Downham, near Bromley, Kent. Bombs were being dropped in this area, but a lot less than in London. Some incendiary bombs dropped in the next road to us in Downham. I went with a friend to go and have a look. These bombs were filled with phosphorous, which is highly inflammable. Some of this substance had been blown into the road, and was still burning. I made the mistake of trying to stamp the flames out, with the result that my shoe was set alight. I quickly took it off, but the shoe was burnt to a cinder. I had to walk home wearing only one shoe. I got a real telling off from mum and dad, as clothes and shoes were rationed, and precious ration coupons would have to be used to buy me a new pair. The bombing began to ease off a lot, I think maybe because the Germans had lost so many planes over Britain and other countries.

One evening, just as it was getting dark, dad and I saw what we thought was a plane on fire. This soon disappeared, but about five minutes later we saw it again, then a little later a third time. Dad said he couldn’t understand why the plane was going round in circles, or why it hadn’t crashed. After about an hour, an announcement was made on the radio that southern England was being attacked by flying bombs. These were unmanned planes filled with a large amount of high explosive. This was what we had seen in the air. The Germans called these V1’s. In Britain they came to be known as doodlebugs, I’m not sure why. These V1’s had a jet engine at the back, and had an exhaust flame coming from them. This is what confused us into thinking it was a plane on fire. The jet engine made a terrible noise, but then it would just stop. This was very scary, because you didn’t know where it would land. Sometimes they would drop straight out of the sky, other times they would glide and explode some distance away. The doodlebugs were arriving at regular intervals, causing terrible damage and killing and injuring large numbers of people. All the schools closed down for safety reasons. Every house in our area had an Anderson shelter in the garden. These were bad enough to go in when the usual air raids were taking place, at least with them the sirens sounded, which gave you time to get into them. With this continual stream of V1’s arriving you had to stay in them day and night. Risks had to be taken by adults to prepare food and drink for their families by going back into the houses. Dad was still working long nights, so mum had to take the risk. Dad couldn’t get to sleep in the shelter, so decided to sleep in the house during the day. The shelters, having been dug deep into the ground, always smelled of damp. If it rained hard, the water would seep in and run onto the concrete floor. The only light available at night was from oil lamps or candles. Another problem was insects, such as spiders, earwigs, moths and other flying pests. As the allied armies advanced through France, they were gradually destroying the launching sites from where the V1’s were being fired. One Sunday afternoon, while we were in the air raid shelter, one of these ‘doodlebugs’ landed about 250 yards away from us. It could not have happened at a worse time, for being a Sunday, most people were at home. Mum’s friend Louise Parsons, who lived in Peckham, had come to spend the weekend with us. As the doodlebugs were coming over about every ten minutes, we were all in the garden shelter at Ballamore Road, Downham. My dad wasn’t at home, I don’t remember where he was. As there had not been a doodlebug arriving for about thirty minutes, Louise said she would make us all a cup of tea. Mum tried to dissuade her, but she insisted that she would be alright. After making the tea, she was walking down the garden path with the teas on a tray, when the doodlebug exploded. It’s engine had stopped long before it hit, so it must have been gliding for some time. The blast lifted Louise off her feet, with the tray of teas, and blew her against the fence. Her arm and leg were grazed and she was badly shaken. The result of the explosion was terrible. A lot of people were killed, many of them children, and dozens more were injured. The explosion destroyed a large number of houses. Our home had windows damaged, and large areas of ceiling came down. It was lucky we were in the shelter, as we would have been injured by flying glass at the very least. A large part of the flying bomb landed in our garden. It measured about three feet by two feet, and landed quite close to our shelter, part buried in the lawn. The authorities came to take it away.

As things were so dangerous, we were on the move again, this time to Salford, on the outskirts of Manchester. This was well beyond the reach of doodlebugs. A neighbour had relatives there, and was taking her three children with her to stay. She told mum that there was accommodation available for us if we wished to go. We all left together a few days later. Manchester and Salford had been heavily bombed by German air raids, as had most of our big cities. Large areas of bombed sites were all around the place where we were staying, however, the raids had now stopped, due to the extreme military pressure being put on Germany. After a period of around three months we returned to Downham, as the doodlebugs had stopped arriving. The government paid contractors to repair minor damage to homes to make them habitable again, ours was classed as minor damage and the house was then fit to live in. We had only been back home a few weeks when the country was under attack from terrible weapons called V2’s. These were huge rockets that travelled at three thousand miles per hour, faster than the speed of sound, so they couldn’t be heard until they exploded. They were much more deadly than doodlebugs, as they carried a huge amount of high explosives. There was no point going to the shelters, as there was no warning of their arrival. This, without doubt, was the most frightening part of the war. There was no defence against them. When they exploded they caused horrendous damage and loss of life. When doodlebugs were arriving you could usually hear them, and have some chance of taking cover, and a lot of them were shot down by our fighter planes, at great risk, before they reached London. One of the V2’s exploded on Woolworths at Lewisham on a Friday afternoon. As Lewisham’s busy outdoor market was right next to Woolworths, there was absolute carnage. Many men, women and children were killed and injured. After five years of war the population was at full stretch. The fighting spirit was immense, through terrible hardships, of which there were many, they kept going.

After the doodlebugs stopped arriving, schools reopened, but were now closing again. It was thought to be unwise to have large numbers of children in one place. The V2’s could be fired from specially constructed vehicles, which could be driven from place to place, making it difficult to locate and destroy them. The first V2’s started falling in September 1944, and continued until the end of march 1945. Over 1300 exploded in London.

The war against Germany ended on the 8th May 1945, which became known as VE Day (Victory in Europe). The war against Japan ended on 10th August 1945 (VJ day). The Germans and the Japanese were on the same side. The war against the Japanese was expected to last a long time, possibly years. However, the Americans dropped two atom bombs on Japan, the first one on Hiroshima on 6th August and the second one on Nagasaki on 9th August. Japan surrendered unconditionally the next day, 10th August. Soon after VJ Day, thousands of children’s street parties took place throughout Britain. We had one in our road. People brought out their dining tables and chairs, lining them up in a long row. All the neighbours contributed towards the food and drink, whether they had children or not. One neighbour brought her piano out into the road, and played for us all. That evening, a large bonfire was lit in the middle of the road, leaving a large burnt area which remained there for years.

Although the war was over, the effects lasted for years. One day, I was on my own, looking for chestnuts in Elmstead woods, about a mile away from home. I was looking under fallen leaves when I saw a cord. I started pulling it, and discovered a German parachute. It has been buried only a couple of inches under the ground, obviously by a German airman trying to hide the fact that he had landed there. It was in a very poor state, but I took a few scraps home. Another day, my sister Maureen had emptied the last of the coal from our coal shed (we were now using electric fires). She had decided to do this so we could keep our bikes in there. She told me that she had found a metal object and had left it in the shed. When I looked, I was amazed to see that it was a German incendiary bomb. It must have landed in the coal yard next to Grove Park railway station. The grabber which picked up the coal to load into sacks must have picked up the bomb too. The sack had been delivered to our house and the coal tipped out. The bomb must have fallen to the bottom, and had more and more coal heaped on top of it over time. Maureen said she had hit it with the shovel a few times when she was clearing the shed, the bomb disposal people came to take it away, and informed us later that it was live. She was very lucky not to have been killed.

After the war was over, rationing continued for many years. This included food, clothes, and fuel (coal, petrol and oil). The last items to be free of rationing were sugar and sweets, in 1954, nine years after the war had finished.

My memories of the war include bad times and good times, but all of them unforgettable times.

Copyright © Calvin White 2015 – All rights reserved

‘It Doesn’t Seem So Long Ago’ a poem by Calvin White

It doesn’t seem so long ago

Off to the country I had to go

From bombers flying overhead

Sleeping in shelters instead of bed

It doesn’t seem so long ago

When Germany was England’s foe

I watched the battles in the sky

Where brave young men were sent to die

When doodlebugs and rockets guided

Were sent to break the undivided

The people of London were not cowered

They stood together with heads unbowed

Sometimes only food for thought

Not the kind that rationing brought

Each small amount we had to eke

To be sure it lasted through the week

It doesn’t seem so long ago

When winters always brought the snow

Never a car would we meet

Whilst playing snow games in the street

Shrimps and winkles for Sunday tea

The muffin man would always be

Ringing his bell with all his might

And the hot chestnut man warmed up the night

Toasting forks, hot buttered toast

All sitting down to the Sunday roast

Bellows pumping, arms aching

Making sure the bread was baking

Hard boiled eggs with hand painted faces

Roll them downhill, everyone chases

Chocolate ones not around any more

Another restriction because of the war

Come Halloween, apples in barrels floating

Hideous masks with faces gloating

Pumpkins, with features that shine

Jacket potatoes and hot ginger wine

Christmas pudding, sixpence hidden

Taste of the mix strictly forbidden

Real holly, home made decorations

Christmas evening, visit friends and relations

For colds, flu or even the croup

Mum’s magic cure was onion soup

The man with the cart totting for rags

Exchanging for goldfish in water filled bags

Hopscotch, fivestones, marbles to play

No television to watch all day

Whips and tops, wooden hoops

Tin soldier armies, I controlled the troops

It doesn’t seem so long ago

When mother was young, and father also

Wartime over, things looking up

Charlton even won the FA cup

It doesn’t seem so long ago

But counting the years, it is you know.

Copyright © Calvin White 2015 – All rights reserved